Impact of Venture in Mission

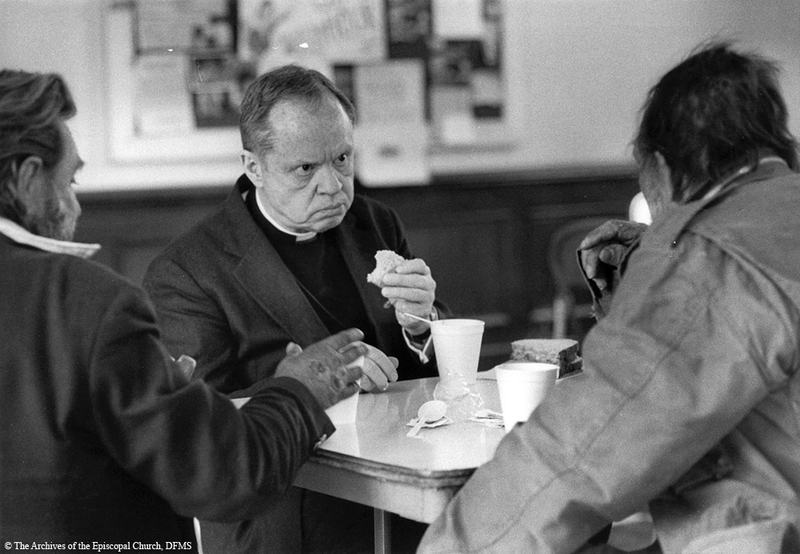

Allin listens intently as he shares a meal at a soup kitchen while in Charleston, SC for an Executive Council meeting in February 1983.

VIM service bulletin depicting six characteristics necessary for “venturing” in the area of church growth, c.1978.

“Some are called to serve in the complex cities, some in rural areas, some in mountain provinces, some on island clusters. In every place we are called to relate to the Lord Christ, to lift up, to restore, to feed and teach and heal, to cheer and to encourage, to help one another serve others.” 71

The VIM fund-raising approach raised money and enthusiasm for mission by linking diocesan and local ministry needs with the national campaign. A fund-raising firm guided the approach with marketing materials, but dioceses had considerable freedom to tailor the campaign and giving opportunities to match local interests. VIM officials found that most dioceses’ initiatives fell into one of several categories: special ministries, community-based ministry for marginalized populations around social concerns (e.g. poverty, housing, etc.), education, lay and ordained ministry development, urban and rural work, health services, and community development. These were new areas of ministry – launching the Church into areas that were not covered adequately by governmental programs, which had in previous decades unmoored the Church from its traditional mission work in city mission, child welfare, and hospital care.

The impact of VIM giving is captured in a sample of the wide array of funded diocesan programs:

• a tutoring program in Chicago

• health clinic outreach in Pennsylvania

• an abused women’s shelter in Indianapolis

• aiding and rehabilitation of offenders in Virginia

• a retirement community in Kanuga

• a rural transportation project in Navajoland

• outreach to the urban elderly in the Twin Cities

VIM funds were also used in the service of the Church’s minority and marginalized populations such as the recruitment of black clergy, training in Hispanic ministries, and expansion and training for the Episcopal Conference for the Deaf. In addition to these domestic projects were many overseas mission endeavors such as literacy in Costa Rica, a new wing at St. Luke’s Hospital in Tokyo, and projects in Tanzania and Uganda. No other mission program before VIM had ever dreamed of extending the Episcopal Church’s reach beyond its own institutional boundaries. It was a stretch that dramatically altered the scope and direction of the Church’s domestic mission.

Examples of the allocation of VIM funds to various domestic and overseas projects:

1977: $3,500,000 in grant funds for the Seminary Consultation on Mission endowment to fund and facilitate education and mission

1979: $100,000 for Native American Theological Association (from the Diocese of Nebraska)

1980: $20,000 for emergency relief and resettlement in Somalia (from the Diocese of Southwest Florida)

1980: $16,100 for the Community Conference Center Project Juba, the Republic of the Sudan (from the Diocese of Pennsylvania)

1980: $18,272.38 for American Council of the St. Luke's International Medical Centre at St. Luke's Hospital, Tokyo (from the Dioceses of North Carolina and Central Pennsylvania)

1981: $500,000 for the National Mission Indian Trust Fund (from The Episcopal Church)

1981: $15,000 for Offender Aid and Restoration of U.S.A., Inc (from the Diocese of Western Massachusetts)

1986: $60,000 for St. Mary's School for Indian Children, Diocese of South Dakota (from The Episcopal Church)