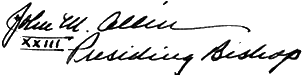

Vows and Vocation

“When the illegal and irregular and invalid ordinations occurred – I say all of those descriptives with intention – when the ordinations in Philadelphia of the women by bishops who were exercising beyond their authority and when women took oaths, and in taking them broke oaths they had made to bishops in good standing of this Church to whom they pledged to be obedient and lawful and follow the canons, as far as I’m concerned those were invalid ordinations. The Church can stand those aberrations at times, but you cannot have a valid ordination if you break a vow to take a vow, particularly if the two vows are both ordination vows. There are many people who hold a contrary opinion to that, but that’s the one I hold.” 51

A Strongly Held Belief

Allin was aware that Port St. Lucie opened the teaching authority of the Church, and his leadership as Chief Pastor, to the threat of skepticism. He wondered to what extent personal conscience should play a part in his, or any individual member’s, acceptance of the Church’s synodical decisions. Did his non-acceptance of women in the role of priest preclude him from carrying out his duties as Presiding Bishop? He pondered the difficulty: “I asked the question: do you have to have all the answers right according to what the General Convention says in order to function in this House, to be Presiding Bishop? And in connection with that, that means, do you have to agree with a fifty-one percent decision by General Convention, do you have to accept that as faith, if you haven’t come to that, as a matter of faith? And if you do, I mean, do you have to do that, for example, to be Presiding Bishop? Do you have to do that to be a member?”52 The answer to that question aside, as the leader of the Church, his actions at Port St. Lucie haunted him throughout his tenure as Presiding Bishop.

The issue of ordaining women proved to be the Achilles’ heel of Bishop Allin’s administration, and the way in which he responded to it overshadowed his successful work in other areas such as race relations, ecumenism, and mission extension. His personal feelings on the matter seemed to have blinded him to what were, ultimately, the profound wishes of the majority of the Church. He had attempted to mask his personal opinion by focusing on canon law and church processes. As was evident in Port St. Lucie, even after the ordination of women had been accepted by General Convention, Allin opposed women in the priesthood as a strongly held belief. He never considered the ordination of the eleven women to be valid, even many years later in his retirement.